If you’re a screenwriter and have wondered, how can I take my screenplay and adapt it to a comic book script? Well, follow along as I show you how I did it.

In this case, it’s for my screenplay Domino Effect, which I began adapting into a graphic novel.

Here is a page-to-page comparison between a screenplay page and the comic page version. Both were created using Final Draft software.

The Screenplay version…

The Comic version…

As you can see, although similar, there are distinct differences between the two. Whereas a screenplay straight forward Scene Heading, Screen Direction, and Dialogue; the comic page is broken into panel descriptions and then dialogue/caption. In the screenplay, the character Domino’s lines are off-camera voice-over (which V.O. signifies). In comic book language that translates as CAPTION. As you may have noticed, the screenplay scene is broken up into moments that are described as Panels. Each Panel is a moment in time, similar to keyframes in animation, think of them as a still frame that visually captures the moment.

At the start of every page, I like listing the number of panels per page. I think of panels as picture frames and the page is the wall. Depending on the size and shape of the picture frames, you have one panel (frame) to fill the page––that’s called a SPLASH PAGE––or you can have as many as 12 or more panels. The more the panels, the smaller they have to be.

As you may have noticed, there are numbers alongside the Domino character’s name. These sequential numbers are meant as a guide for the Letterer. A Letterer is a person who creates and formats the reading material on the pages of art: the word and thought bubbles with text, as well as captions that signify third-person or voice-over narrative.

Regarding Panel descriptions, as you can see it is very similar to the screenplay version. Keep in mind that this won’t always be the case. Some moments of screen direction may vary in length when transposed to comic scripts. In screenplays you can describe a moment in time with one simple sentence, whereas to suggest the same moment with sequential art may take multiple panels.

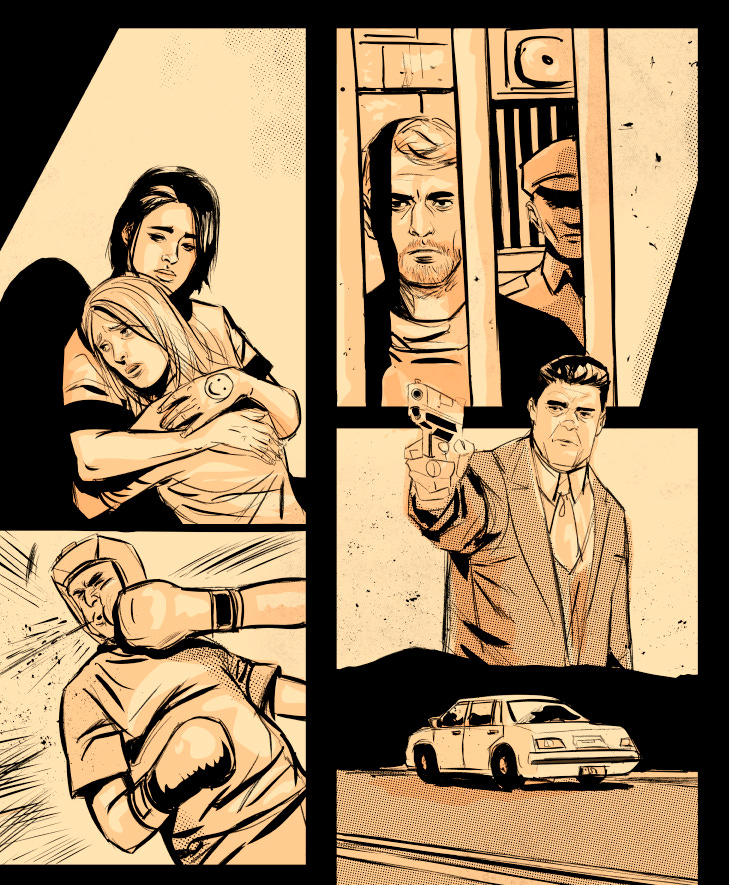

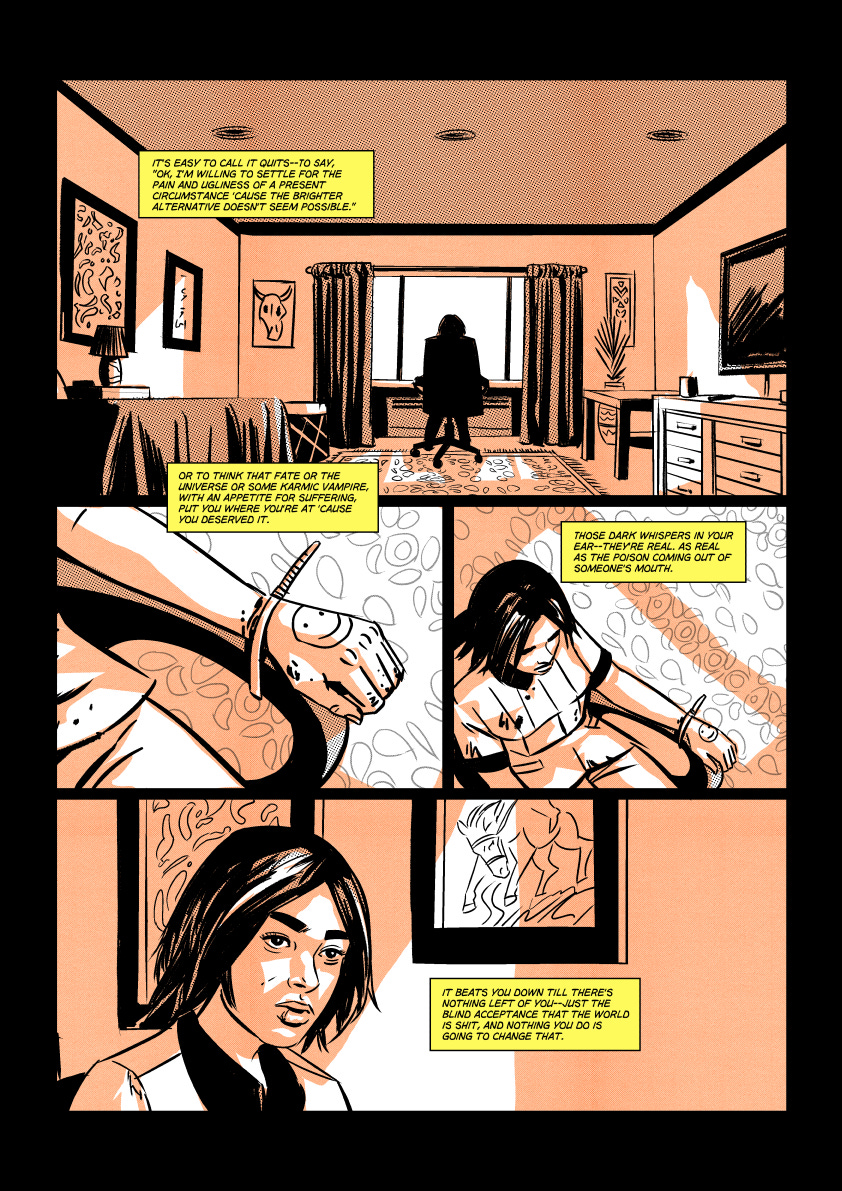

Here is the page illustrated from the comic script.

When adapting a screenplay to a comic script, as a writer you may at times have to go granular with your description. In a sense, you are directing the scene, describing to the artist in finer detail what you envision in a panel. In some cases, more detail than you would have in a screenplay. In a sense, as the writer, you are the director conveying your vision to the artist. The artist, in comparison to film, would be the cinematographer, production designer, costume designer, and a few other production jobs too, all rolled up into one.

I think of it as a small production company capable of making high-budget movies with the smallest crew possible.

Moving on to page two, if you may have noticed on the bottom of page one of the screenplay page we see the start of a new scene, which we don’t see on the comic script. As you may have guessed, it’s not a page-for-page translation when it comes to length. The INT. RUNDOWN APARTMENT – DAY in the screenplay version will appear on page two of the comic version.

Once again, here is a side-by-side comparison of the screenplay page to the comic book page.

Once again, the screenplay page and the script page don’t line up content for content with the comic script. In this case, the 1 screenplay page resulted in 2 comic script pages. Incidentally, there’s an additional line from the character Courtney “With what money? We’re barely getting by,” that I included in the comic script that you’ll notice didn’t land on page 2 of the screenplay––It’s on page 3 of the screenplay, which I didn’t include here.

As you can see the numbers start back up, delineating each line of dialogue. For some reason with Final Cut, the software I used to transpose my screenplay to the comic script, it keeps resetting the numbers back to 1 for each page. Not a big issue, but I personally prefer the numbers to continue chronologically. Which is why I usually use another software called Scrivener to write my comic scripts. Scrivener’s numbering doesn’t reset back to 1 on subsequent pages.

That said, since most screenwriters I know work in Final Draft, I wouldn’t sweat it. Final Draft is perfectly fine for comic scripts. My reason for usually using Scrivener is that I like creating a guide for the letterer that coincides with the script. It’s something most writers won’t have to worry about unless they’re an anal-retentive writer/artist like me farming out the lettering duties.

Suffice it to say, since I’m the writer, illustrator, and letterer of this book, I’ll know where to place the word content.

Also, did you notice the SFX on page 3 of the comic script? That signifies Sound Effects, which, as a writer, you can include or not depending on your preference.

Here is what the next two pages look like. Compare them to the screenplay and comic scripts.

One of the keys to adapting your screenplay into a comic script is to remember to be as specific to your vision as you write descriptions in your panel. The illustrator will have their interpretation of your text, so as much as you can communicate that vision while allowing the artist to be true to their creativity is essential.

Look out for future posts about creating comics!

For paid subscribers, be sure to continue on and check out a script-to-page comparison of the Issue One teaser of my graphic novel series Domino Effect.

Until next time!